Post by phil on Nov 16, 2006 15:05:34 GMT -5

The Sunday Times November 12, 2006

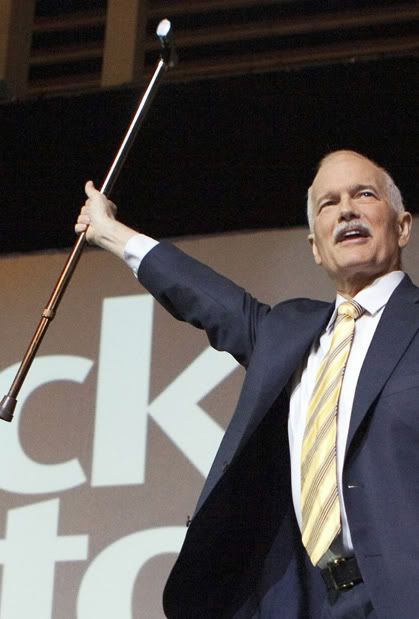

That way son

After his election humiliation George Bush has slunk back to Dad for help. It's Shakespeare meets Freud, says Andrew Sullivan

The events of last week in America have an almost Shakespearean quality to them. It’s like some ghastly conflation of Richard II’s doom-laden “Down, down, I come” and Richard III’s “winter of our discontent”. Richard II is how Bush would like the world to see him — a king of noble motives brought low by injustice and fate. Richard III is . . . well, ask Karl Rove, the hunch in W’s back.

At the centre of this epic psycho-political drama is a royal family of sorts in a war for survival: the Bush dynasty, a story of a father and his son, their tortured relationship and what they have had to do to survive.

Last week George W Bush was forced back — once again — to the protective arms of his father. They call the first President Bush “Poppy” in the family, and it captures both the authority and the slight daffiness of the 41st president. His first son always lived in his shadow — both deeply admiring him and deeply resenting him, the way dauphins often do their monarchs.

In his own presidency, with the Yankee Bush clan reforged in the desert of Midland, Texas, Dubya tried to chart his own course, create his own destiny, become his own man. He would have two terms, not one. He would never raise taxes. And he would remove Saddam, not just corner him; liberate Iraq, not just contain it.

Last week the dream collapsed in the sands of Anbar and the voting booths of the Midwest. The first son, who always wanted to make a name for himself, to escape the suffocating legacy of a presidential father, was forced by the American people to go back to Poppy.

BY nominating Robert Gates to the Pentagon, Bush Jr was reduced to asking one of his father’s closest friends to clean up the mess. What was Gates’s last job? As president of Texas A&M University, Gates hosted Poppy’s own presidential library. What was his previous claim to fame? Poppy had appointed him CIA director. Poppy himself had been CIA director — manoeuvred into the shell-shocked institution after Vietnam by a wily young Donald Rumsfeld in the Ford administration. Gates was a CIA director’s CIA director. He was Poppy’s Poppy.

Is it possible to come up with a figure other than Gates more closely connected to the patriarch and not the dauphin? Actually, yes: James Baker. By asking Baker, another close confidant of the senior Bush, to head up a commission to solve the Iraq disaster, the president was forced again to return to the wise men of his prudent father’s circle.

The irony last week was even worse for the 43rd president. By firing his defence secretary, Bush was also firing his dad’s old enemy. He was surrendering one of his dad’s foes and replacing him with one of the old man’s closest pals.

In his latest book, State of Denial, Bob Woodward is clear about the long-held animosity between Poppy and Rummy. They couldn’t stand each other. “Bush senior thought Rumsfeld was arrogant, self-important, too sure of himself and Machiavellian. He believed that in 1975 Rumsfeld had manoeuvred President Ford into selecting him to head the CIA. The CIA was at perhaps its lowest point in the mid-1970s. Serving as its director was thought to be a dead end . . . Rumsfeld had also made nasty private remarks that Bush was a lightweight, a weak cold war CIA director who did not appreciate the Soviet threat and was manipulated by secretary of state Henry Kissinger.”

If you want to know why Bush Jr held onto Rumsfeld longer than any sane person should have, one clue lies in the paternal relationship. Surrendering Rumsfeld means that Poppy was right. Not just right about Rumsfeld’s skills and nasty streak. Right about the biggest things: war and peace, country and honour. Rummy was in some ways the personification of the son’s refusal to be his father. Rummy was the prickly, querulous, impolitic businessman, everything Poppy was not.

By picking one of his father’s old nemeses to head the Pentagon in 2000, W was also telling the old man to stay out of his affairs. And Poppy did. As Woodward also recounts, Bush Sr told his friend Prince Bandar of Saudi Arabia: “I had my turn. It is his turn now. I just have to stay off the stage . . . I will not make any comment vis-à-vis this president, not only out of principle but to let him be himself.”

W was indeed himself, which makes the failure now that much harder. Last week was a moment of complete humiliation. Wednesday, for Bush Jr, must have been the most crushing psychological moment in his presidency.

Of course, this kind of analysis would be dubbed by the president mere psychobabble. But the facts are plain.

George W was the first son, but never the favoured one, of the Bush dynasty. Jeb, his younger brother, was always going to be president. W was the loser, the joker, the wastrel. But W was also, in his heart, desperate to emulate his father, while too driven by his own ego to listen to him. He desperately both wanted approval and just as desperately wanted to be free and independent.

It is self-evidently hard to be the son of a vice-president and president. It is hard to feel that every business deal you ever made was not because you were shrewd but because your father was powerful. It is hard both to support your father’s career and also to resent him. But that is the story of this president and, in part, of this administration.

When W was campaigning with his father in 1992, he described the oedipal conflict himself. At the New Orleans convention that year W confided to the Houston Chronicle that he was ambivalent about his father’s re-election campaign. He said his father’s defeat might be good for him, according to the invaluable early biography of Bush by Bill Minutaglio, First Son.

Then he brought himself up short and said to the reporter: “That is a strange thing to say, isn’t it? But if I were to think about running for office and he was president, it would be more difficult to establish my own identity. It probably would help me out more if he lost.”

The struggle between father and son began early. W was his mother’s boy, his father distant. “My father doesn’t have a normal life,” he once told a classmate, according to Minutaglio. “I don’t have a normal father.”

He was also a rebel. After a period at Yale and in the National Guard, W spent his twenties partying. One night when he was 26, he had

been out drinking and had driven home. He had drunkenly barrelled his car into a neighbour’s rubbish bin, which had become attached to the car, and Bush drove down the street with the bin making a hell of

a racket.

He pulled up, walked into the house, and was told that his father wanted to see him in the family den immediately. It was only a few weeks after the death of the über-patriarch Prescott Bush, W’s grandfather. But the young man was in a feisty mood, as the journalist David Maraniss revealed way back in 1989.

“I hear you’re looking for me,” W said to Poppy, slurring his words. “You wanna go mano a mano right here?”

Jeb, the favourite son, intervened. He told his parents that W had just been accepted by Harvard Business School, something W had kept from them. They were stunned, and the potentially violent stand-off was defused.

“You should think about that, son,” Poppy said. “Oh, I’m not going,” W replied. “I just wanted to let you know I could get into it.”

Of course, W went. And in that tortured interaction, all the subsequent psycho-drama can be found. Supremely rebellious and yet deeply loyal, all W wanted was to please and yet outdo his dad. In the end he achieved neither.

W went to the Ivy League but hated it for what he saw as the American elite’s snootiness and liberalism. At his news conference last Wednesday the president looked at the press corps and saw the same type of people. “Why all the glum faces?” he sneered bitterly. They reminded him of everything he loathed in his dad.

But the love was there as well. A family friend, Joe O’Neill, even ascribed Bush’s decision at 40 to stop drinking to the paternal factor. “He looked in the mirror and said, ‘Some day I might embarrass my father. It might get my dad in trouble.’ And boy, that was it. That’s how high a priority it was,” O’Neill told Minutaglio. “He never took another drink.”

W surpassed his dad by actually becoming a businessman. But his oil company exploits never worked out. He kept trying to find the magic oilfield that would reward his investors, but it never arrived. And there was always the suspicion that his family’s money and his father’s political power greased the wheels.

The more W tried to get past his father’s legacy the more it tracked him. Here is a passage from Minutaglio’s book that bears rereading this week. It’s about Bush’s early attempts to strike a big oilfield in Texas.

“The project was simply too large for him, and it was like putting a steel cap on a dream . . . Bush was extremely disappointed at losing . . . the chance to be deeply, independently capitalised without having to rely on his uncle’s investors. ‘We had never found the huge liberator,’ is what Bush once said to a Dallas writer.”

It’s almost too poignant a parallel to the present. Bush so wanted to be a huge liberator in another desert. But the wells were dry.

When Bush failed in business, his family contacts kept him financially afloat. He was kept on boards and bailed out of trouble by people eager to keep in his father’s good graces.

His connections were also inextricable from his successful bid to be governor of Texas. But when he won re-election as governor, he felt empowered for the first time as a political force independent of his father.

He had found Karl Rove, who had honed his skills in the gutters of Southern political campaigning. And he had an ease with people that his father lacked and a shrewdness he inherited from his mother.

It was a powerful combination, and when W ran for the presidency it was both to avenge his father’s defeat at the hands of Bill Clinton and at the same time a way to show how he was not like his father at all. Ideologically he was much closer to the religious right, he was adamant on taxes, he wasn’t prudent fiscally, and he wasn’t timid in the world at large.

By putting Rumsfeld, his father’s enemy, in the Pentagon he sent a signal that he was his own president and his own man. Gaining the presidency was emulating his father. But regaining it was the final moment when Bush surpassed his one-term dad. It was also the moment when this administration started falling apart at the seams.

W loves boldness. It’s his greatest strength and his deepest weakness. When it came to Iraq, his decision was laden with memory. His father had fought a war against Saddam. Its hallmarks were a vast multinational coalition, huge numbers of troops and distinctly limited goals. The son’s war would be different.

With Rumsfeld in the Pentagon, it would be with an extra-light force, with far fewer allies, and far more ambitious. It would not only defang Saddam, it would establish democracy. If his father always had trouble articulating the “vision thing”, as he once memorably put it, the son was all vision. In fact, the vision blinded him to the reality.

You can forgive W for the innovative, lightning decapitation of the Baghdad regime. In fact it was a stroke of genius. But you cannot forgive him for the hubris afterwards, for having no plan for the post-invasion, no troops to keep order, no strategy for everything his father had once worried so much about. His father would never have done such a thing. Wouldn’t be “prudent”, would it?

As Woodward recounts in his new book, the parents were worried all along. At a black-tie dinner on the eve of invasion, Barbara Bush took aside a Washington friend, David Boren, a former Democratic senator who had been the chairman of the select committee on intelligence during Poppy’s presidency.

“You always told me the truth,” Barbara opened, drawing Boren aside for a private chat.

“Yes, ma’am,” Boren replied.

“Will you tell me the truth now?”

“Certainly.”

“Are we right to be worried about this Iraq thing?”

“Yes. I’m very worried.”

“Do you think it’s a mistake?”

“Yes, ma’am,” Boren replied. “I think it’s a huge mistake if we go in right now, this way.”

“Well, his father is certainly worried and is losing sleep over it. He’s up at night worried.”

“Why doesn’t he talk to him?”

“He doesn’t think he should unless he’s asked,” Barbara Bush said.

This time there was no Jeb to intervene to avert a father-son clash. And the father was too decent and too loyal to force one.

Poppy’s closest allies did what they could before the war to stage an intervention. Brent Scowcroft, Poppy’s former national security adviser, wrote a newspaper article warning against war in Iraq. Scowcroft was a realist of the old Poppy school. He had no illusions about spreading democracy among Arabs; he’d been happy to deal with Saddam as a bulwark against Iran; he was content to stand back in 1991 as Saddam, left in power, murdered countless Shi’ites and Kurds, because the United States was not prepared to occupy what Churchill once called the “ungrateful volcano” of Iraq.

Scowcroft was Condoleezza Rice’s mentor. He was part of the Bush famiglia, governed by the clan’s code of omerta. For him to be disloyal in public was a warning shot from the old man. But the son didn’t listen. Too many of us were deaf.

There is another irony. Poppy was prudent but not bold. W was bold but not prudent. If Poppy had been as bold as his son back in 1990 and had actually invaded Iraq, the coalition would indeed have been greeted as liberators in Baghdad. There would even have been enough troops to succeed in an occupation. The anti-American suspicions that the Shi’ites retained from their bitter experience of being abandoned in 1991 and the rapid deterioration in Iraq’s civil society during the sanctions regime of the 1990s might never have come about.

The ironies are painful. If the father had been more like the son in 1990 the world might now be a very different place. And if the son had been more like the father in 2003, had responded to obvious errors and brought sufficient allies and troops to the task, he might have succeeded as well.

But the tragedy of history is that we never know what might have been: 1990 wasn’t 2003, and Poppy wasn’t W.

W stuck with Rumsfeld’s vision even when no one else would. Poppy stuck to caution even when he had a historic opportunity to remake the Middle East before the toxin of Islamism could become more potent. Each was his own man and each, in his own way, therefore failed. Except that the consequences of W’s failure are immeasurably greater than Poppy’s.

The truth about this president is that he still loves and reveres his father. This cathartic moment in American and world history might also be a catharsis within the Bush family. The ranks are already closing. With Gates and Baker now back in the fold, Poppy’s faction has solidified behind W’s. They want to help him out, to rescue his presidency, to rebalance American power in the world and to carve something from the wreckage in Iraq.

Last week the American people forced the family intervention. They knew what they were doing. If you combine W’s shrewdness with Poppy’s wisdom you might have the beginning of a new day in world politics. This Shakespearean drama is not over. We have merely finished Act IV. W has two more years. The Democrats will force him to move domestically to the centre, and Daddy’s team will not abandon the son in his hour of need. Their price was Rumsfeld’s head, and they now have it on a platter.

What they will do is not yet knowable. Much is on the table. As recently as two years ago Robert Gates authored a Council on Foreign Relations paper advocating direct negotiations with Iran. Baker’s Iraq Study Group has already deemed the goal of democracy impossible there. The American people, for their part, do not want defeat or a Vietnam-style retreat in Iraq. They just want a sane strategy, shorn of delusion, fanaticism and arrogance.

Whether Bush has the strength to reconcile with his father at this moment and do what is necessary is also unknowable. These are not characters in a play. They are still human beings, as unpredictable and inscrutable as Shakespeare saw them. The American voters just shifted the underlying plot; and the Iraqi people have their own painful decisions to make and loyalties to break.

Act V, in other words, is about to begin.